Small Craft Stories: Let 'Em Run Drift Boats

posted by

We’re on the lookout for stories from every corner of the boating world—small boat builders, fix-it shops, gear makers, and everyone in between. No matter the size of your operation, we’d love to feature you in a piece and share your story with our community. Shoot us an email at tim@smallcraftsales.com and tell us a little about yourself.

Some kids grow up playing baseball in the yard. Brian Berry at Let 'Em Run Drift Boats grew up ripping up and down the Teton River in lodge boats he was barely big enough to start, leaving the motor running all day because if it died, he was dragging that sucker home. That upbringing at Teton Valley Lodge didn’t just make him a guide it hardwired him into the DNA of river boats themselves. Today, Brian is the guy behind Let ’Em Run, building some of the most interesting guide-bred craft out there: foam-cored, vacuum-infused drift boats, skiffs, and hybrid raft setups designed to solve the stuff guides actually complain about, boats that are too heavy, interiors that eat fly line, and platforms that can’t get into the good water. We talked with Brian about growing up inside one of the West’s most storied lodges, why their boats exist in the first place, and how a lifetime of rowing, breaking, fixing, and refining boats turned into a full-blown boat company.

This week we're featuring Let 'Em Run Drift Boats and the owner Brian Berry who also grew up at and owns the Teton Valley Lodge.

Small Craft Sales: You grew up inside one of the most storied fishing lodges in the West. What was your earliest memory of boats and rivers?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: That’s a good question. I can’t really pinpoint a single “earliest” memory because it was just our life. When I was born, we lived at the lodge in one of the cabins. The next year my dad built our house about a hundred yards away from the lodge. Now my house is a stone’s throw from my parents’ old house. So it’s been pretty immersive my entire life. It’s the only place I’ve ever worked.

As a kid, I was just always around the lodge, not really understanding what was going on. It wasn’t something special to us—it was just life. Summers were incredibly busy. My dad was gone constantly, guiding every day. We rarely saw him during the season. My mom was always working too—she did the books, payroll, shuttles, cooked breakfast and dinner one night a week, cleaned cabins, managed the staff. They were both nonstop.

We were just there all the time in the summer—either working a little or completely on our own, running around. Some of my best memories are just being kids outside all day. We fished, hunted, messed around. We weren’t serious fishermen yet, but we were always on the water.

We had a boathouse with these old Teton boats and little eight- and nine-horse Mercury outboards. We were way too small to start them ourselves, so we’d go find one of the guides—usually Tom Fenger, who still guides at the lodge and is basically like my uncle—and ask him to come start the motor for us. Then we’d just run up and down the Teton River all day, chasing ducks, trying to fish, swimming, getting into trouble.

We’d leave the motor running all day because if it died, we were in big trouble. If we ran out of gas or sucked up mud or grass and killed it, we’d end up walking the boat home or dragging it down the bank. It happened more than once.

It was just this footloose, free little world. Me and my best friend Stevie—Steve Pehrson, my dad’s partner’s son—we just felt like kings of the world. Running boats, riding dirt bikes, shooting squirrels, doing whatever we wanted. It was amazing. It really was.

Small Craft Sales: Your family has been guiding and running the lodge for generations. Did building boats feel inevitable, or did it evolve out of necessity?

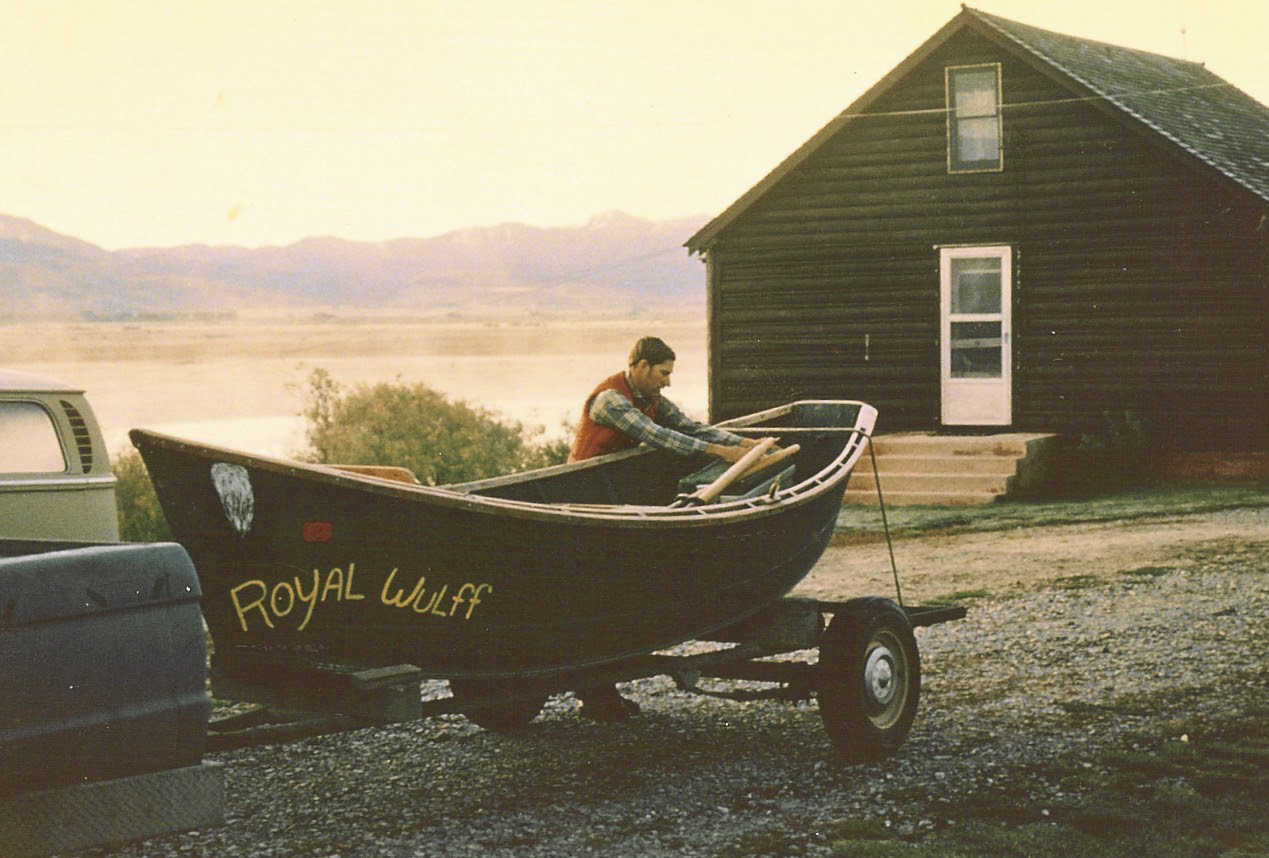

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: Building boats started long before I was old enough to be useful in any way. In the early to mid-80s they began building fiberglass boats. Before that, they built some wooden boats and what we called “Teton boats,” mostly just for guiding on the Teton River here in the valley. Before those, they were using Keith Steele wooden boats, which they absolutely loved. They were amazing boats.

A Keith Steele boat in heavy water in the 70s.

I never guided out of the Keith Steele boats, but I fished out of them with my dad. They took a lot of maintenance, though. Being wooden boats, they were constantly being repaired—taken apart, varnished, joints sealed, leaks fixed, painted. They beat the hell out of them. Every boat we had back then was green. All green. You always knew Teton Valley Lodge boats because of that. We don’t do that anymore, and I kind of miss it.

Eventually they started experimenting with fiberglass. There was a guy down in Menan, Idaho—outside of Idaho Falls, near the confluence of the Henry’s Fork and the South Fork—named Muns. He brought up a fiberglass boat with a foam core and showed it to my dad and John. At that time, fiberglass boats were big, heavy, bulky, and not very maneuverable—nothing like the Keith Steele boats they loved. Those heavy boats weren’t something they could guide out of.

Another big factor was logistics. Back then, most guides were college kids or ski-bum, fish-bum types who didn’t own vehicles or boats. It wasn’t like today where you see drift boats everywhere. Boats were rare. The lodge had a fleet of boats and a fleet of cars, and to save money on shuttles, gas, and vehicles, they would double and triple stack boats on trailers. To do that, you needed lightweight boats.

When the Muns guys brought up that foam-cored boat, my dad and John were blown away. They beat on it with a hammer and saw how strong it was. They bought a couple, and then two of the guides at the time—Tom Fenger and Chris Nelson—decided they could make it better. They built the first one in a garage and brought it out. From there, it just evolved.

My dad had a great design eye. He wasn’t college educated, but he had been rowing boats his entire life and knew exactly how they needed to work. They patterned a lot of the design after those Keith Steele boats, but always used foam core and built them by hand. Between my dad and Tom—who is an incredibly smart guy—they kept tweaking hull shapes, rocker, layouts, repairing them, breaking them, fixing them, and improving them year after year.

It was all necessity. They needed a boat that was lightweight, durable, and maneuvered the way they wanted. They took those boats everywhere. They didn’t use rafts—they hated rafts. They dragged boats into the Lower Mesa Falls, into the Narrows of the Teton, down Cardiac Canyon on the Henry’s Fork, through big water everywhere. Just like they had done with the wooden boats before.

They were never trying to sell boats. They didn’t want to be in the boat business. They just wanted to guide, fish, and have the best possible tool to do the job they loved.

Small Craft Sales: Let ’Em Run clearly comes from a guiding background. At what point did you realize the boats you were building had potential beyond your own lodge?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: The moment we really realized the boats had potential beyond our own outfitting business was when guides started taking them home in the off-season. This was mainly with the rafts at first. Guides were borrowing them on their days off or keeping them for the winter to fish out of on their own. When guides want to use something on their personal time, you know you’ve got something good.

With the drift boats, we’ve always loved them. We never wanted to row anything else. We always knew they were the best boats to guide out of, but they were very bare-bones, utilitarian guide boats for a long time. To make them viable for customers outside the lodge, we needed to refine and perfect the creature comforts—things that consumers care about that guides don’t always need.

We worked on that for years. One of the advantages we have is that we run around 30 guides who are using these boats every day and constantly giving feedback—what works, what doesn’t, what they like and hate. That kind of real-world testing is invaluable.

They’re still not perfect, and they probably never will be. We’ll keep refining and changing things forever. But where they are right now is really solid. We know the construction is durable because of how hard we use them. We know the hull design rows and maneuvers exceptionally well and gets you into places other boats can’t. And now the interiors are clean, beautiful, and fish incredibly well.

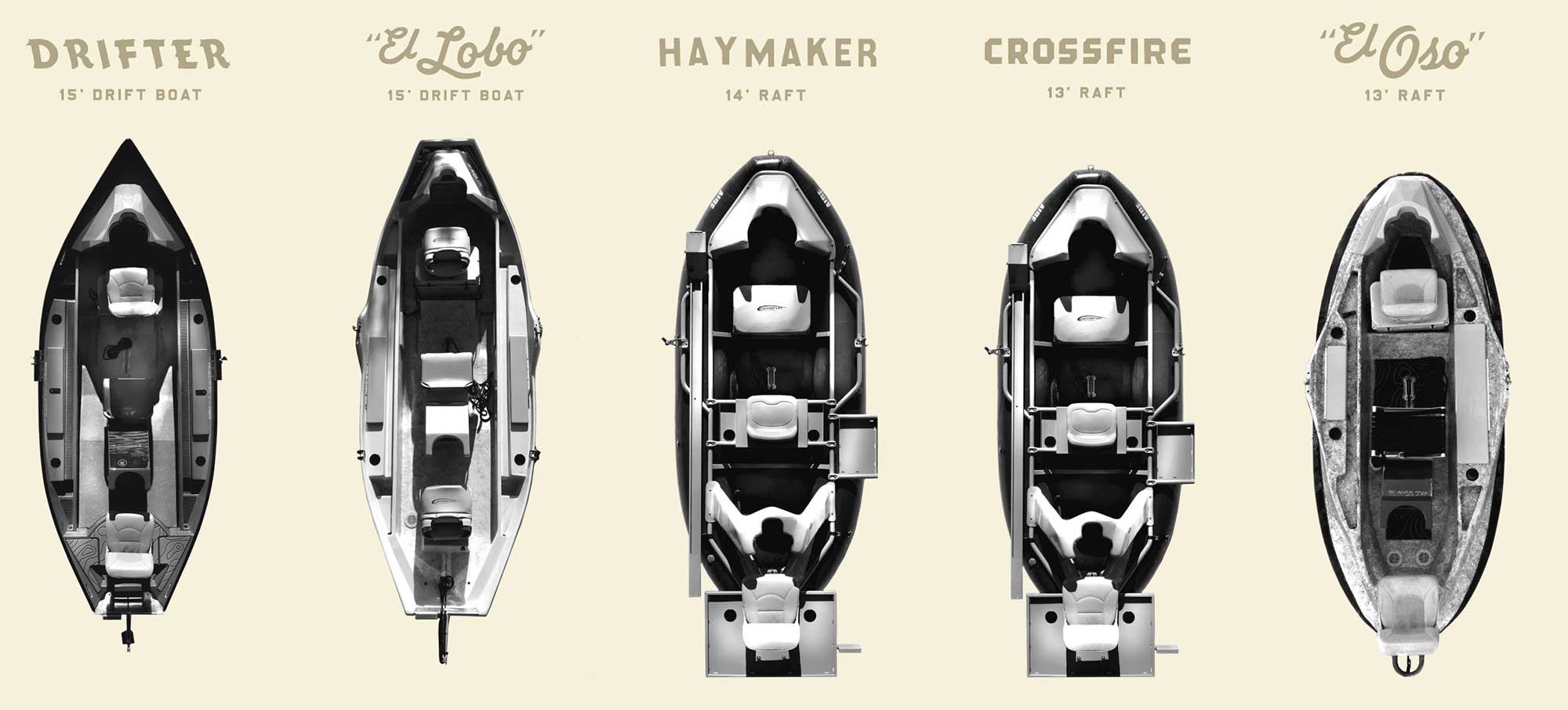

Small Craft Sales: Let ’Em Run makes 5 different boats right? Can you give us a VERY brief rundown of each one?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: We’ll start with the Crossfire. The Crossfire was our first raft that we felt was truly ready for sale. It’s a 13-foot raft and it’s what we guide out of at Teton Valley Lodge in the Narrows, on the Henry’s Fork through Cardiac Canyon, and on lower sections of the Henry’s Fork with diversion dams and portages. We also use it in the winter when we need to drag gear in and out of the river.

What sets the Crossfire apart is the snag-free frame. There are no bolts or fasteners holding the frame together—it’s a one-piece welded frame. It has a solid fiberglass floor that creates a true standing platform, fiberglass knee braces front and back, storage in the guide seat, a boat tray holder, and all the creature comforts you can get in a metal-framed raft. It fishes more like a drift boat than almost any metal-framed raft out there.

Next is the Haymaker. The Haymaker is essentially the same boat as the Crossfire, just stretched to 14 feet. It has all the same characteristics and features, but it’s built for people who need more room—especially for overnighters or carrying additional gear. Everything great about the Crossfire, just in a longer platform.

Then there’s the Drifter. The Drifter is a classic drift boat–style dory with a pointed bow. It’s 15 feet long. The hull weighs about 150 pounds, and the fully rigged boat comes in around 350 pounds. There’s a huge amount of storage—under the bow, under the rear knee brace, on both sides next to the guide, and underneath the guide seat.

One unique feature is the back end. It’s designed so you can slide large dry bags, lunch coolers, and other gear underneath the rear seat, completely out of the way. That keeps things from catching your line and makes gear easy to access throughout the day.

The Drifter is our best all-around, everyday fishing boat. It’s super comfortable, extremely clean inside, lightweight, and very maneuverable. It’s built in three pieces—the hull, the floor, and a combined rod holder, front knee brace, and rear seat mold—which makes it very easy to clean. It drains beautifully, stays snag-free while fishing, and is comfortable for long days on the water.

Next is the Lobo. The Lobo is a skiff-style drift boat with super low sides. It has all the comforts of the Drifter, but the low profile makes it ideal for rivers where wind is a big factor and big whitewater isn’t. It’s great on rivers like the Henry’s Fork, the Madison, the Bighorn, Gray Reef, and similar fisheries.

The Lobo is built in two pieces—one interior mold and one exterior mold—and comes in at around 300 pounds fully rigged. It has lots of storage, excellent rod storage for both forward- and rear-facing rods, and will hold rods up to 13 feet. The interior is extremely clean, and the knee braces are removable, so it can easily be set up as either a sit-down or standing boat. If you’re looking for stealth and wind performance, this is the boat you want.

And maybe the star of the show is the Oso. The Oso is a one-piece carbon fiber raft frame that’s extremely lightweight, extremely clean, and completely snag-free. It feels like you’re in a drift boat, but you’re in a raft. The frame itself weighs about 73 pounds fully rigged with lids, seats, and everything else—including a YETI cooler. The entire boat comes in around 125 pounds, and the inflatable tubes weigh about 90 pounds. It’s an incredibly lightweight, comfortable setup. You get dry feet, a solid standing platform, self-bailing performance, comfortable knee braces, cup holders everywhere, good storage for a raft, built-in rod holders, and built-in fly box storage. It’s the most comfortable raft you could ever fish out of. With low water conditions becoming more common across Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, this is a boat a lot of people are going to wish they had. It allows guides to keep clients comfortable while still running low, skinny water.

Small Craft Sales: Your drift boats have a pretty distinctive look and build. Can you explain that and give a brief explanation of the construction process? I know you use a pretty specific sandwich construction with vacuum-infusion.

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: The look really comes down to our main man Curtis over at Neighborhood. He’s an incredible designer and has done all of our graphics and branding, which we really appreciate. We wanted the boats to have a true Western feel. We’re a Western company, born in the mountains and in Teton Valley, and we wanted the branding to reflect that. I think he absolutely nailed it.

One of the cool things we do is that our graphics are printed directly onto the fiberglass and inlaid into the boat. They’re not decals or stickers, so they don’t rub off or wear off over time. It’s a pretty unique process that gives the boats a distinct look and lets us do some really cool things visually that help set them apart.

The construction is really what makes the boats special, though. All of our boats are vacuum infused. Infusion is a process that gives you one of the lightest and strongest composite structures you can build—stronger than hand-laid construction. You end up with a lighter boat and a stronger boat at the same time. It also eliminates a lot of human error because it’s a closed-mold process. If everything is laid up according to protocol, you get the same boat every single time.

We use vinyl ester resin, which is a very high-quality resin that’s much more durable and wear-resistant than many other options. The fabrics are all engineered materials—quadraxial and biaxial fabrics—that are cut specifically for each boat. There are no scraps or filler pieces thrown in anywhere.

The boats are built using a true sandwich construction: fiberglass, then closed-cell foam, then fiberglass again. That sandwich creates a composite that’s extremely stiff, very strong, and very lightweight. When it’s infused, it all becomes one chemically bonded, sealed composite—hull and interior together.

That’s really the reason we build them the way we do. We guide hard, so the boats have to be durable. And they need to be lightweight so we can row hard, work hard, get into more spots, and get to more fish. The design is cool, the graphics are cool, and the layout is clean and comfortable—but what really sets these boats apart is how strong and light they are at the same time.

Small Craft Sales: Your hybrid raft/drift boat designs are particularly interesting. What problem were you trying to solve when you began developing those?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: The main problem we were trying to solve with the rafts is exactly that—they’re different. Drift boats and skiffs all share some similarities across brands, and while I think our construction, weight, and durability make ours unique, what really sets our company apart from most drift boat builders is our raft designs.

We guide on water where drift boats simply became an issue. At the time, we weren’t selling drift boats, and some of our guides were using boats from other companies that just couldn’t go certain places. The water was too complex. They couldn’t maneuver fast enough, slow down enough, or safely get through some of the rougher sections. So we had to have rafts for those areas.

The problem is that fishing out of rafts, for the most part, kind of sucks. Customers hated it, and guides hated rowing them. You either had a super light, simple frame that the guide liked to row, but the customer was miserable—wet feet, nowhere solid to stand, line catching on everything—or you had a super complex, heavy raft that was difficult for the guide to row. The customer might be a little happier, but the line was still catching everywhere, and it still wasn’t a great experience.

So the goal was really to solve that problem on both sides. We wanted guides to stop complaining about having to take rafts into certain places, and we wanted customers to actually enjoy fishing out of them.

It took us a lot of years, and we failed several times. Eventually, we landed on two designs that really worked. The Crossfire and Haymaker share one design philosophy, and the Oso is a completely different approach, but both solved the same core problems. They aren’t drift boats—but they’re as close to a drift boat as we’ve been able to accomplish, and I think as close as anyone’s been able to get.

That’s given us a ton of flexibility. Our guides are happy rowing them, and our customers actually enjoy fishing out of them. The main issues we were trying to solve were line snagging, wet feet, lack of stability while standing, uncomfortable knee braces, and line catching on everything. Those were the problems we were really focused on fixing.

Small Craft Sales: How much of Let ’Em Run’s evolution has come from intentional engineering versus simply responding to real-world time on the water?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: We’re pretty old school. I’m not a very techie guy, so it really hasn’t been a lot of engineering in the traditional sense. We never set out to build boats to sell. We were just trying to build boats that we wanted to guide out of and fish out of—boats that would make us better guides at the end of the day.

This wasn’t something that was engineered in a shop or on a computer. It was built over years and years of time on the water, with input from dozens upon dozens of guides and fishermen. It was constant feedback—“I don’t like this about this boat,” or “this doesn’t work,” or “this thing broke,” or “this is too heavy,” or “this needs to be stronger.”

A lot of it was just solving problems we ran into every single day. My line is catching on this knee brace—how do we eliminate that? My rod is getting scratched when I put it in this holder—how do we fix that? My customer is uncomfortable standing or sitting here—how do we improve that? Or the boat won’t get into the holes I want, or I don’t feel safe taking it into bigger water, or it’s getting blown around because the sides are too high.

It’s been a constant process of identifying those issues and trying to solve them—sometimes failing, sometimes improving, sometimes having to go back and rethink things. We definitely haven’t solved every problem, and we never will. There will always be more improvements to make.

But it’s been a very focused, very intentional effort driven almost entirely by real-world experience—our own experience, and the experience of our guides and fellow fishermen who use these boats every day—and trying to come up with the best solutions we can to make better boats for what we do on the river.

Small Craft Sales: What makes a great drift boat in your mind? What separates a truly exceptional boat from an average one?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: In my mind, the number one thing that makes a boat great is weight. If a boat is too heavy, it doesn’t matter how nice the interior is. If you can’t get it into the places you need to go or slow it down enough to properly fish the water, it just doesn’t work for us. The way we fish and the way we work water requires a light boat, and that’s always been our driving goal.

That said, there’s a balance. You can make a boat super light, but then it’s going to break. Or you can make it super light and strip out all the comforts, and then it’s not enjoyable to fish out of. So there’s always a balancing act—getting the boat as light as possible while still keeping it durable and comfortable enough that you’re not constantly repairing it or sacrificing the fishing experience.

For me, those three things are what matter most: lightweight, durable, and comfortable. If you can get all three right, you’ve got a great boat.

Small Craft Sales: How have the rivers around Teton Valley shaped your approach to boat design?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: The rivers around Teton Valley have had a huge impact on our boat designs. That’s our office—that’s where we work every day.

The Drifter is really focused on the South Fork. The South Fork is a big river. It doesn’t have classic whitewater, but it has huge whirlpools, heavy seams, a lot of velocity, and a lot of power. It can be intimidating. You need a boat that isn’t too low-sided or you’ll suck a rail under and swamp it. It has to be stable enough to handle the wild seams you hit when you’re sliding down banks or coming out of channels. That river has absolutely shaped the Drifter. If we’d never guided the South Fork, it would be a very different boat.

The Lobo skiff is heavily influenced by the Henry’s Fork and the Teton River. Those fisheries demand stealth. Wind is a big factor. You need something low-profile that stays out of the wind, can slip under bridges, draft extremely shallow water, and move quietly. That’s really what drove the evolution of the skiff.

The rafts are strongly influenced by Cardiac Canyon on the Henry’s Fork and the Narrows of the Teton—two places we love to guide. That’s where those boats were tested and developed. They needed to handle fast, technical whitewater, big moves, and serious abuse. We drag boats into mountain slides, beat them up on rough access points, and push them hard in those sections.

Every aspect of our boats has been shaped by those three rivers. They’ve all played a major role in how and why our designs are the way they are.

Small Craft Sales: You balance running a historic lodge alongside building boats. How do those two worlds influence each other?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: Running the lodge and building boats really go hand in hand. We’ve been making boats for a long time, and the whole reason we started building them was so we could guide better.

What makes the lodge great is our guides. They work incredibly hard, and having the right boats allows them to work even harder and be better at what they do. At the lodge, everything we think about is centered around giving our customers the best experience possible, and number one on that list is great fishing.

So we build boats to help us guide better. That’s really the birth of Let ’Em Run—it comes directly from the way we guide and our desire to guide at the highest level we can. Building boats that allow us to do that and running the lodge are completely intertwined.

Small Craft Sales: Correct me if I’m wrong, but you guys have a “boat house” of sorts under the lodge where you can row boats off the river through a small slough and store them for the evening—kind of like a lake situation.

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: Yeah, we do have a boathouse on the Teton River. There’s always been a channel there to store boats. I believe the first boathouse was built sometime in the 1940s or 50s—I’m not exactly sure—but it’s been part of the lodge for a long time. You can row boats in and out through that channel directly to the river.

We use a very different kind of boat there that we call Teton boats. They wouldn’t really be suitable for many other places, but they work perfectly on the Teton. In a lot of ways, they’re an homage to my great-grandpa Alma, who started the lodge. Those are the boats they guided out of back then.

There’s definitely a nostalgic element to it, but it’s not just nostalgia—they truly work incredibly well on that piece of water. It’s the only way we like to fish the Teton there. They’re kind of unique: about 20 feet long, roughly three feet wide, almost like a square, flat-bottomed canoe. Originally, they were built for trapping, and when they started guiding fishermen and hunters, that’s just what they had, so that’s what they used.

They’re very simple boats—no frills at all—but they work amazingly well on that special piece of water that we’re lucky enough to live on.

Small Craft Sales: What’s something most people misunderstand about drift boats—or “river boats” in general?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: One thing I think a lot of people misunderstand—especially about rowing a drift boat—is how much of the work should come from your legs and your back, not your arms.

We build a large foot brace into our boats for that reason. If you’re rowing properly, your arms shouldn’t be exhausted at the end of the day. You should be using your whole body. It’s more about leaning forward and backward with your body and pushing off with your legs, rather than sitting upright and pulling only with your arms.

Rowing that way gives you a lot more strength, a lot more torque, and much better endurance. It allows you to slow the boat down effectively, really work the water, and get into places you simply can’t if you’re just rowing with your arms. When done right, it’s more efficient and far less tiring.

Small Craft Sales: What still excites you about boats after all these years?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: I love building boats. I’ve always loved building things in general, thinking through problems, and figuring stuff out. In a lot of ways, boats are the same thing for me as fishing—they’re a puzzle.

When you approach a river and fish are doing something, you have to figure it out. What bugs are they on? What depth are they feeding at? What kind of water are they sitting in? What’s their mood today? Do they want bigger flies, smaller flies, mayflies, stoneflies? You dial it in, and then you fine-tune it even more—maybe it’s a PMD, but they want it a little lighter olive, maybe it needs to be a cripple, an emerger, a dun, or a spinner. All those little idiosyncrasies are what make fishing interesting.

Boat building is the same way. It’s about identifying problems and solving them. What’s not working? What could be better? How can we make this easier, more efficient, or more enjoyable for guides and anglers who are out there every day rowing and fishing?

That problem-solving aspect is what keeps it exciting for me—trying to make something better and improve the experience of being on the river doing this amazing sport of fly fishing.

Small Craft Sales: What’s next for Let ’Em Run?

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: What’s next for Let ’Em Run is that we’re moving into our brand-new factory in Victor, Idaho. It’s a huge step for us. The building is about 15,000 square feet, and it’s an incredible space. It’s going to allow us to really ramp up production and start getting boats out all over the West—and eventually across the rest of the country—to fly fishermen who are excited about a new boat, a new style, and a different way of thinking about boat building.

Along with the factory, we’re also putting in a fly shop. It’ll be about 3,500 square feet, and it’s going to be a beautiful, fully stocked shop with everything guides and anglers need, including boat accessories and gear to be successful on the water.

That’s what’s next in the short term. Long term, who knows—the sky’s the limit. We’re excited to keep innovating, keep building new boats and new products, and keep finding ways to spend more time on the water and catch more fish.

Small Craft Sales: Lastly — when you’re in the boat shop, what are you listening to? Give us three albums you’re jamming to right now.

Let 'Em Run Drift Boats: We listen to a lot of Spotify in the shop. There’s a heavy rotation of Outlaw Country—Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, all those guys. We also listen to a lot of Chris Stapleton and similar stuff in that same vein.

We mix in a lot of classic rock too—usually a Led Zeppelin station on Spotify. That turns into Pink Floyd, The Stones, all those great bands. And then we also listen to a lot of Joe Rogan podcasts.

So it’s usually one of three things coming out of the Turtlebox in the corner of the shop: Rogan, classic rock like Zeppelin and Floyd, or Outlaw Country with Willie, Waylon, Chris Stapleton, and everything in between.